Introduction

I see this all the time, in practice and recommended online. What should I do with the water from my downspouts, or that’s pooling on my patio or driveway? Too often, landscape and concrete contractors, friends and family, suggest the installation of a “french drain” to collect and deal with this water. Sadly, this nearly always is the wrong solution to these issues and the end result when implemented is typically a failed drain system… Maybe not today or tomorrow, but in the near-term.

In Utah, Idaho and most other states, municipal code requires that runoff from residential and commercial properties be handled on site, preferably as a way to recharge ground water reservoirs. This includes water from sidewalks, the roof and the landscape. Some water will end up in municipal storm drain systems, but the majority of this water should be limited to runoff that simply can’t effectively be captured and managed onsite due to proximity to the road or sidewalk. Municipal storm drain systems simply aren’t designed to handle runoff from all houses and landscapes adjacent to them, so they quickly become overwhelmed when they’re required to do so.

Common Solutions

Over the years, I’ve seen three common solutions implemented with varying degrees of success and failure… It’s the failures, expense and frustration that have led to this article. So what are the most common solutions I see?

- Allowing downspout water, and water from landscapes and sidewalks to just run wherever it naturally wants to go. This situation might be ok in some small number of cases, but in others leads to foundation issues, flooded basements, illegally depositing runoff into municipal drain systems, the destruction of landscape features due to pooling, oversaturation of soil, frost heave issues, etc. Even worse, it can cause issues for neighbors that are left to deal not only with their own water, but with yours.

- Downspouts that run into corrugated drain lines, which terminate with pop up emitters in lawns or rocky areas of a landscape. This actually might be a great option, but can become problematic in yards with little or no slope (or negative grade), insufficient area for the water to be distributed and absorbed, soil that doesn’t allow for rapid enough absorption, etc. Additionally, pop up emitters often become damaged or lost when installed in grassy or heavily planted areas, particularly where those performing regular maintenance are unaware of or indifferent to their existence and the need to maintain them.

- Downspouts and other surface water sources that are run directly into a sort of french drain, This is by far the worst of the 3 scenarios being discussed in this section. By design and purpose, french drains are intended to absorb water from their environment, the ground, and move it to another, better location to be dealt with. The pipe used to collect the water is typically filtered by a sock and surrounded by gravel. The gravel is typically burrito-wrapped by a filtering fabric as well. All of this filtering is to prevent contaminants from entering and clogging the pipe. To be extra clear, the intended inlet is the filtered perforations in the pipe, which allow water to enter the pipe mostly free of silt and debris. The water is then quickly able to flow through a newly created path of least resistance (the clean pipe) to a preferred place where it can be dealt with more effectively. To introduce silt and debris directly to the inlet of the pipe, and then to expect the pipe itself to distribute the water into the ground, is a recipe for rapid failure. The pipe becomes silted in, the perforations become clogged, the volume of water the system can handle decreases rapidly and failure occurs

What is the right solution?

As with most things, there isn’t one right solution, but let’s look at some alternatives to french drains and discuss some of the pros and cons of each. Please note that this isn’t intended to be an exhaustive discussion on water residential storm water runoff, but is intended for an audience of a typical, residential homeowners and their landscapers, that are dealing with typical residential yard spaces.

Short drain with a pop-up emitter

Already mentioned above, this can be a fantastic solution under the right circumstances. So, what are those circumstances? It depends on the inlet source, but these systems are essentially installed with both the inlet and the outlet on the surface of the yard. This means that there needs to be enough pressure, typically from gravity, that the water, including any sediment that flows into the pipe with it, will have enough pressure to be ejected on the outlet side of the pipe. If the inlet is a downspout, the pressure generated by the fall from the roof might be enough under medium to heavy rain conditions, where sufficient continuous flow occurs, to carry as much water and sediment through to the outlet as is entering the outlet. Significant impacts can be: a) Water volume b) The pressure generated by the fall from the roof weighed against the overall length of the pipe between the inlet and the outlet sides of the pipe c) The use of corrugated vs smooth wall pipe d) The existence of sediment or debris stuck in the pipe e) An unobstructed outlet

A common installation scenario is the use of a corrugated pipe, because it’s affordable and flexible. The pipe extends from the inlet, often a drain on a patio or from a downspout, 25-40’ into a yard. The fall between the inlet in the outlet is often less than 2% because people like to have level/flat yard space near their house. Increased pipe length with insufficient fall represents an increase in resistance, which directly represents decreased potential for throughput (lower flow rates). If the flow decreases sufficiently, sediment can enter the system, but might not exit at the same rate. Increased sediment further increases resistance and further decreases flow even more, until the sediment completely clogs the pipe.

I once performed demolition on a yard up that had three abandoned, corrugated pipes that at one point or another had all been connected to the same downspout. We couldn’t find the outlet for any of the three until we’d commenced with the demolition, at which point we learned that all three also had abandoned pop-up emitter elbows attached to them. The three were completely filled with sediment and water was simply overflowing the gutters above. The house was about 12 years old at the time. The previous owners must not have cut their grass consistently, then mulched when they did. The emitters were completely lost in the process.

What can be done to mitigate these issues and successfully use this solution? Keep your pipe length short, use a smooth walled pipe (PVC) instead of corrugated when dealing with shallow grades, and simply don’t bother trying this approach if the pipe has to run uphill or for long distances.

While we’re at it, there are some places you absolutely don’t want to emit this water: a) Near concrete patios or a sidewalk b) Near fence posts, if you can help it, c) Right next to your house or other structures d) Right next to your irrigation box or other important infrastructure e) Near retaining walls

Extremely saturated soil near structures and infrastructure is what we’re trying to avoid here, but people often overlook landscape structures. Your fence is a structure that’s just as susceptible to overly saturated soil as anything else. Modern vinyl fence posts are rarely set below the frost like. Wooden posts will rot more quickly in saturated soil. Saturated soil that freezes and thaws (often called frost heave) can knock fence posts, gate posts and retaining walls out of alignment.

In ground trampoline holes

Trampoline holes can be an amazing place to deposit water, under the right circumstances. There are a number of pros, cons and considerations:

- Trampoline holes often become natural garbage repositories. Wind blows trash and debris into them, kids drop toys and junk down in there, grass clippings and leaves magically appear during maintenance, etc. The last thing you want is a bunch of trash, leaves, grass clippings and trash under your trampoline, all sitting in standing water for days, weeks or months on end. Nasty. Smelly.

- You’ll likely want to dig the hole out a bit deeper than normal and add a bunch of gravel. It might be easier to maintain if you add some landscape fabric with pea gravel over the top of it. Just a thin layer.

- You might want to consider some kind of grate or cover on the outlet side of the pipe which then might need to be checked on occasion for clogs. While it might be tempting to just leave a 5” pipe open, small animals might take the opportunity to create nests for themselves.

- Trampoline holes are often pretty deep. If your yard is flat and you’re worried about not having enough fall between the pipe’s inlet and outlet, using a trampoline hole might solve that problem for you, as the pipe’s trench can be buried with additional slope across the run. You’ll want to make sure to pack some gravel around the outlet to ensure erosion doesn’t become an issue.

- This bears repeating… if your soil doesn’t drain well, standing water that’s essentially on the surface of your backyard, though it may be hidden in your trampoline hole, is not ideal.

- You might have to take the mat off of your trampoline on occasion, or at least partially remove it, in order to clean and inspect this space, the drains, etc.

I’ve used trampoline holes for this purpose on a number of occasions with great success. The holes are typically large enough to handle substantial rain events and maintenance is typically pretty easy. This is essentially a way to have a retention pond in your yard, which is rarely an option outside of commercial and industrial landscapes.

Drywells, infiltration trenches and storm chambers

Inground trampoline holes are great, but they aren’t for everyone. If you’ve arrived at this point in the article and still haven’t found your ideal solution, a drywell, infiltration trench or storm chamber might be your best option. The good news is that these aren’t ditch effort solutions, they’re great solutions that I personally prefer over the others in this article!

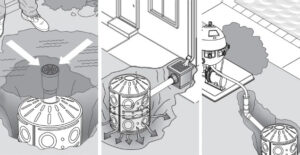

The theory behind these solutions is the creation of an underground area where a volume of water can be deposited and left to percolate into the ground at whatever speed the native soil allows this process to naturally occur. They’re usually installed 2-10 feet under the ground and can be joined together to increase capacity. Systems like this are common on commercial properties, but affordable residential solutions exist from companies such as NDS.

Drywells

Drywells are typically cylindrical barrels, usually with a capacity of 25 to 50 gallons. They’re often made of a strong plastic or polycarbonate-like material. They can be connected together, either by using pipes or by stacking, to further increase capacity.

Though connected wells are probably more common, some drywells support being stacked. This is of particular benefit if the desired installation location has minimal space available, but the installer has the ability to create a deep hole. The stacking option might also be perfect for scenarios where a solution is required within an existing landscape and disruption to existing landscape features needs to be minimized. In such a case, a mini excavator or skid steer with an auger attached might be able to use a 30” or 36” bit to create the hole. If a drainline already exists, to the location, it might be possible to connect it directly to the new drywell, further minimizing the need to disrupt existing, installed landscape.

In the image above, on the left, note that an overflow emitter has been installed leading directly out of the top of the well. This is optional, but provides the additional benefit of an access point for inspection and clean out. Eventually the drywell may collect debris. With the overflow extending out from the top of the well, the user can use a pressure washer to jet water down into the well to break up and loosen debris and silt, then use a wet/dry shop vac to clear the well.

With this type of solution in place, homeowners should enjoy many years of worry free use. Should an issue arise, and with annual inspection (recommended), ongoing maintenance costs should be minimal and failure rates nearly non-existent.

Infiltration Trenches and Storm Chambers

Infiltration trenches and storm chambers are typically installed south of a substantial catch basin, These solutions are designed to absorb and disperse large volumes of water back into the ground, but are best considered after the water entering them has had silt and debris mostly removed. Small catch basins that exist on the inlet side of a downspout are a great idea, but often require more maintenance than expected and may be insufficient for large volumes of water. A drywell might effectively act as a catch basin, with water entering on one side of the well then, if necessary, depositing debris into the bottom of the well and allowing water to exit on the far side into an infiltration trench or storm chamber. The primary consideration here is the ability to easily clean the system out when needed. Typical infiltration trenches and storm chambers are difficult to clean out without excavation, which often means replacement.

Some might say, well an infiltration trench sounds an awful lot like a french drain. Let’s look at the NDS description of their infiltration “French Drain” so we can make a reasonable comparison to what is often installed by local landscapers: Engineered French drains are 10′ bundles of Poly-Rock aggregate with or without corrugated drain pipe. Bundles are available in 7″, 10″ and 15″ diameters, with or without 3″, 4″ or 6″ pipe, respectively. A standard infiltration trench consists of a 10″ bundle with 4″ pipe atop two 15″ aggregate-only bundles, providing over 100 gallons of detention volume. That’s a lot of pipe and a lot of volume, in a small area. Again though, this type of system is assuming that the inlet to the system has been filtered of most debris and sediment!

Conclusion

While a variety of options are available, it’s important to understand the pros and cons of each one, as well as what a proper installation might look like for the one you select. Most residential landscapers and concrete contractors are aware of the pop-up emitter option. As a result, they frequently favor that approach. The fact that it’s common doesn’t mean that it’s always the right answer, and doesn’t mean that it’s always the best idea.

Water management requires a bit of thought and planning, but isn’t particularly complicated. With the correct equipment, these installations can often occur within hours and are absolutely something a DIY loving homeowner can safely tackle!

At Bonum, we have the equipment you need to complete this job, as well as the work required to complete the rest of your landscape installation! We’re happy to discuss your project with you, consult with you on the best equipment solutions to fit your needs, and even help you find the products you need to complete your installation. In a small number of cases we perform contracting, but we’re always willing to recommend you to an expert that can help if we’re too busy